Chapter 18 Factor Analysis

Factor Analysis is much like PCA in that it attempts to find some latent variables (linear combinations of original variables) which can describe large portions of the total variance in data. There are numerous ways to compute factors for factor analysis, the two most common methods are:

- The principal axis method (i.e. PCA) and

- Maximum Likelihood Estimation.

In fact, the default method for PROC FACTOR with no additional options is merely PCA. For some reason, the scores and factors may be scaled differently, involving the standard deviations of each factor, but nonetheless, there is absolutely nothing different between PROC FACTOR defaults and PROC PRINCOMP.

The difference between Factor Analysis and PCA is two-fold:

- In factor analysis, the factors are usually rotated to obtain a more sparse (i.e. interprettable) structure varimax rotation is the most common rotation. Others include promax, and quartimax.)

- The factors try to only explain the “common variance” between variables. In other words, Factor Analysis tries to estimate how much of each variable’s variance is specific to that variable and not “covarying” (for lack of a better word) with any other variables. This specific variance is then subtracted from the diagonal of the covariance matrix before factors or components are found.

We’ll talk more about the first difference than the second because it generally carries more advantages.

18.1 PCA Rotations

Let’s first talk about the motivation behind principal component rotations. Compare the following sets of (fabricated) factors, both using the variables from the iris dataset. Listed below are the loadings of each variable on two factors. Which set of factors is more easily interpretted?

The difference between these factors might be described as ``sparsity". Factor Set 2 has more zero loadings than Factor Set 1. It also has entries which are comparitively larger in magnitude. This makes Factor Set 2 much easier to interpret! Clearly F1 is dominated by the variables Sepal.Width (positively correlated) and Petal.Length (negatively correlated), whereas F2 is dominated by the variables Sepal.Length (positively) and Petal.Width (negatively). Factor interpretation doesn’t get much easier than that! With the first set of factors, the story is not so clear.

This is the whole purpose of factor rotation, to increase the interpretability of factors by encouraging sparsity. Geometrically, factor rotation tries to rotate a given set of factors (like those derived from PCA) to be more closely aligned with the original variables once the dimensions of the space have been reduced and the variables have been pushed closer together in the factor space. Let’s take a look at the actual principal components from the iris data and then rotate them using a varimax rotation. In order to rotate the factors, we have to decide on some number of factors to use. If we rotated all 4 orthogonal components to find sparsity, we’d just end up with our original variables again!

irispca = princomp(iris[,1:4],scale=T)## Warning: In princomp.default(iris[, 1:4], scale = T) :

## extra argument 'scale' will be disregardedsummary(irispca)## Importance of components:

## Comp.1 Comp.2 Comp.3 Comp.4

## Standard deviation 2.0494032 0.49097143 0.27872586 0.153870700

## Proportion of Variance 0.9246187 0.05306648 0.01710261 0.005212184

## Cumulative Proportion 0.9246187 0.97768521 0.99478782 1.000000000irispca$loadings##

## Loadings:

## Comp.1 Comp.2 Comp.3 Comp.4

## Sepal.Length 0.361 0.657 0.582 0.315

## Sepal.Width 0.730 -0.598 -0.320

## Petal.Length 0.857 -0.173 -0.480

## Petal.Width 0.358 -0.546 0.754

##

## Comp.1 Comp.2 Comp.3 Comp.4

## SS loadings 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00

## Proportion Var 0.25 0.25 0.25 0.25

## Cumulative Var 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.00# Since 2 components explain a large proportion of the variation, lets settle on those two:

rotatedpca = varimax(irispca$loadings[,1:2])

rotatedpca$loadings##

## Loadings:

## Comp.1 Comp.2

## Sepal.Length 0.223 0.716

## Sepal.Width -0.229 0.699

## Petal.Length 0.874

## Petal.Width 0.366

##

## Comp.1 Comp.2

## SS loadings 1.00 1.00

## Proportion Var 0.25 0.25

## Cumulative Var 0.25 0.50# Not a drastic amount of difference, but clearly an attempt has been made to encourage

# sparsity in the vectors of loadings.

# NOTE: THE ROTATED FACTORS EXPLAIN THE SAME AMOUNT OF VARIANCE AS THE FIRST TWO PCS

# AFTER PROJECTING THE DATA INTO TWO DIMENSIONS (THE BIPLOT) ALL WE DID WAS ROTATE THOSE

# ORTHOGONAL AXIS. THIS CHANGES THE PROPORTION EXPLAINED BY *EACH* AXIS, BUT NOT THE TOTAL

# AMOUNT EXPLAINED BY THE TWO TOGETHER.

# The output from varimax can't tell you about proportion of variance in the original data

# because you didn't even tell it what the original data was!18.2 Ex: Personality Tests

In this example, we’ll use a publicly available dataset that describes personality traits of nearly Read in the Big5 Personality test dataset, which contains likert scale responses (five point scale where 1=Disagree, 3=Neutral, 5=Agree. 0 = missing) on 50 different questions in columns 8 through 57. The questions, labeled E1-E10 (E=extroversion), N1-N10 (N=neuroticism), A1-A10 (A=agreeableness), C1-C10 (C=conscientiousness), and O1-O10 (O=openness) all attempt to measure 5 key angles of human personality. The first 7 columns contain demographic information coded as follows:-

Race Chosen from a drop down menu.

- 1=Mixed Race

- 2=Arctic (Siberian, Eskimo)

- 3=Caucasian (European)

- 4=Caucasian (Indian)

- 5=Caucasian (Middle East)

- 6=Caucasian (North African, Other)

- 7=Indigenous Australian

- 8=Native American

- 9=North East Asian (Mongol, Tibetan, Korean Japanese, etc)

- 10=Pacific (Polynesian, Micronesian, etc)

- 11=South East Asian (Chinese, Thai, Malay, Filipino, etc)

- 12=West African, Bushmen, Ethiopian

- 13=Other (0=missed)

- Age Entered as text (individuals reporting age < 13 were not recorded)

-

Engnat Response to “is English your native language?”

- 1=yes

- 2=no

- 0=missing

-

Gender Chosen from a drop down menu

- 1=Male

- 2=Female

- 3=Other

- 0=missing

-

Hand “What hand do you use to write with?”

- 1=Right

- 2=Left

- 3=Both

- 0=missing

options(digits=2)

big5 = read.csv('http://birch.iaa.ncsu.edu/~slrace/LinearAlgebra2021/Code/big5.csv')To perform the same analysis we did in SAS, we want to use Correlation PCA and rotate the axes with a varimax transformation. We will start by performing the PCA. We need to set the option ```scale=T} to perform PCA on the correlation matrix rather than the default covariance matrix. We will only compute the first 5 principal components because we have 5 personality traits we are trying to measure. We could also compute more than 5 and take the number of components with eigenvalues >1 to match the default output in SAS (without n=5 option).

18.2.1 Raw PCA Factors

options(digits=5)

pca.out = prcomp(big5[,8:57], rank = 5, scale = T)Remember the only difference between the default PROC PRINCOMP output and the default PROC FACTOR output in SAS was the fact that the eigenvectors in PROC PRINCOMP were normalized to be unit vectors and the factor vectors in PROC FACTOR were those same eigenvectors scaled by the square roots of the eigenvalues. So we want to multiply each eigenvector column output in pca.out$rotation (recall this is the loading matrix or matrix of eigenvectors) by the square root of the corresponding eigenvalue given in pca.out$sdev. You’ll recall that multiplying a matrix by a diagonal matrix on the right has the effect of scaling the columns of the matrix. So we’ll just make a diagonal matrix, \(\textbf{S}\) with diagonal elements from the pca.out$sdev vector and scale the columns of the pca.out$rotation matrix. Similarly, the coordinates of the data along each component then need to be divided by the standard deviation to cancel out this effect of lengthening the axis. So again we will multiply by a diagonal matrix to perform this scaling, but this time, we use the diagonal matrix \(\textbf{S}^{-1}=\) diag(1/(pca.out$sdev)). \

Matrix multiplication in R is performed with the \%\*\% operator.

fact.loadings = pca.out$rotation[,1:5] %*% diag(pca.out$sdev[1:5])

fact.scores = pca.out$x[,1:5] %*%diag(1/pca.out$sdev[1:5])

# PRINT OUT THE FIRST 5 ROWS OF EACH MATRIX FOR CONFIRMATION.

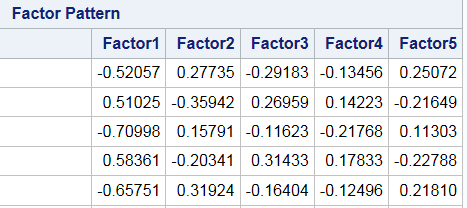

fact.loadings[1:5,1:5]## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5]

## E1 -0.52057 0.27735 -0.29183 0.13456 -0.25072

## E2 0.51025 -0.35942 0.26959 -0.14223 0.21649

## E3 -0.70998 0.15791 -0.11623 0.21768 -0.11303

## E4 0.58361 -0.20341 0.31433 -0.17833 0.22788

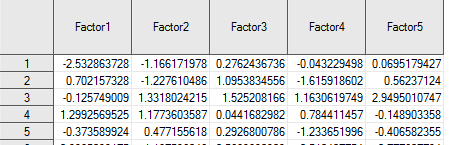

## E5 -0.65751 0.31924 -0.16404 0.12496 -0.21810fact.scores[1:5,1:5]## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5]

## [1,] -2.53286 -1.16617 0.276244 0.043229 -0.069518

## [2,] 0.70216 -1.22761 1.095383 1.615919 -0.562371

## [3,] -0.12575 1.33180 1.525208 -1.163062 -2.949501

## [4,] 1.29926 1.17736 0.044168 -0.784411 0.148903

## [5,] -0.37359 0.47716 0.292680 1.233652 0.406582This should match the output from SAS and it does. Remember these columns are unique up to a sign, so you’ll see factor 4 does not have the same sign in both software outputs. This is not cause for concern.

Figure 18.1: Default (Unrotated) Factor Loadings Output by SAS

Figure 18.2: Default (Unrotated) Factor Scores Output by SAS

18.2.2 Rotated Principal Components

The next task we may want to undertake is a rotation of the factor axes according to the varimax procedure. The most simple way to go about this is to use the varimax() function to find the optimal rotation of the eigenvectors in the matrix pca.out$rotation. The varimax() function outputs both the new set of axes in the matrix called loadings and the rotation matrix (rotmat) which performs the rotation from the original principal component axes to the new axes. (i.e. if \(\textbf{V}\) contains the old axes as columns and \(\hat{\textbf{V}}\) contains the new axes and \(\textbf{R}\) is the rotation matrix then \(\hat{\textbf{V}} = \textbf{V}\textbf{R}\).) That rotation matrix can be used to perform the same rotation on the scores of the observations. If the matrix \(\textbf{U}\) contains the scores for each observation, then the rotated scores \(\hat{\textbf{U}}\) are found by \(\hat{\textbf{U}} = \textbf{U}\textbf{R}\)

varimax.out = varimax(fact.loadings)

rotated.fact.loadings = fact.loadings %*% varimax.out$rotmat

rotated.fact.scores = fact.scores %*% varimax.out$rotmat

# PRINT OUT THE FIRST 5 ROWS OF EACH MATRIX FOR CONFIRMATION.

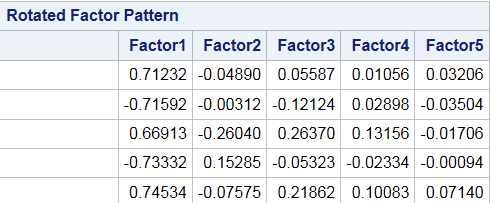

rotated.fact.loadings[1:5,]## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5]

## E1 -0.71232 -0.0489043 0.010596 -0.03206926 0.055858

## E2 0.71592 -0.0031185 0.028946 0.03504236 -0.121241

## E3 -0.66912 -0.2604049 0.131609 0.01704690 0.263679

## E4 0.73332 0.1528552 -0.023367 0.00094685 -0.053219

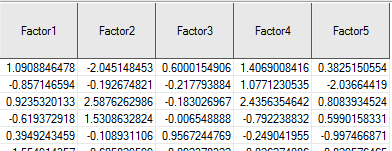

## E5 -0.74534 -0.0757539 0.100875 -0.07140722 0.218602rotated.fact.scores[1:5,]## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5]

## [1,] -1.09083 -2.04516 1.40699 -0.38254 0.5998386

## [2,] 0.85718 -0.19268 1.07708 2.03665 -0.2178616

## [3,] -0.92344 2.58761 2.43566 -0.80840 -0.1833138

## [4,] 0.61935 1.53087 -0.79225 -0.59901 -0.0064665

## [5,] -0.39495 -0.10893 -0.24892 0.99744 0.9567712And again we can see that these line up with our SAS Rotated output, however the order does not have to be the same! SAS conveniently reorders the columns according to the variance of the data along that new direction. Since we have not done that in R, the order of the columns is not the same! Factors 1 and 2 are the same in both outputs, but SAS Factor 3 = R Factor 4 and SAS Factor 5 = (-1)* R Factor 4. The coordinates are switched too so nothing changes in our interpretation. Remember, when you rotate factors, you no longer keep the notion that the “first vector” explains the most variance unless you reorder them so that is true (like SAS does).

Figure 18.3: Rotated Factor Loadings Output by SAS

knitr::include_graphics('RotatedScores.png')

Figure 18.4: Rotated Factor Scores Output by SAS

18.2.3 Visualizing Rotation via BiPlots

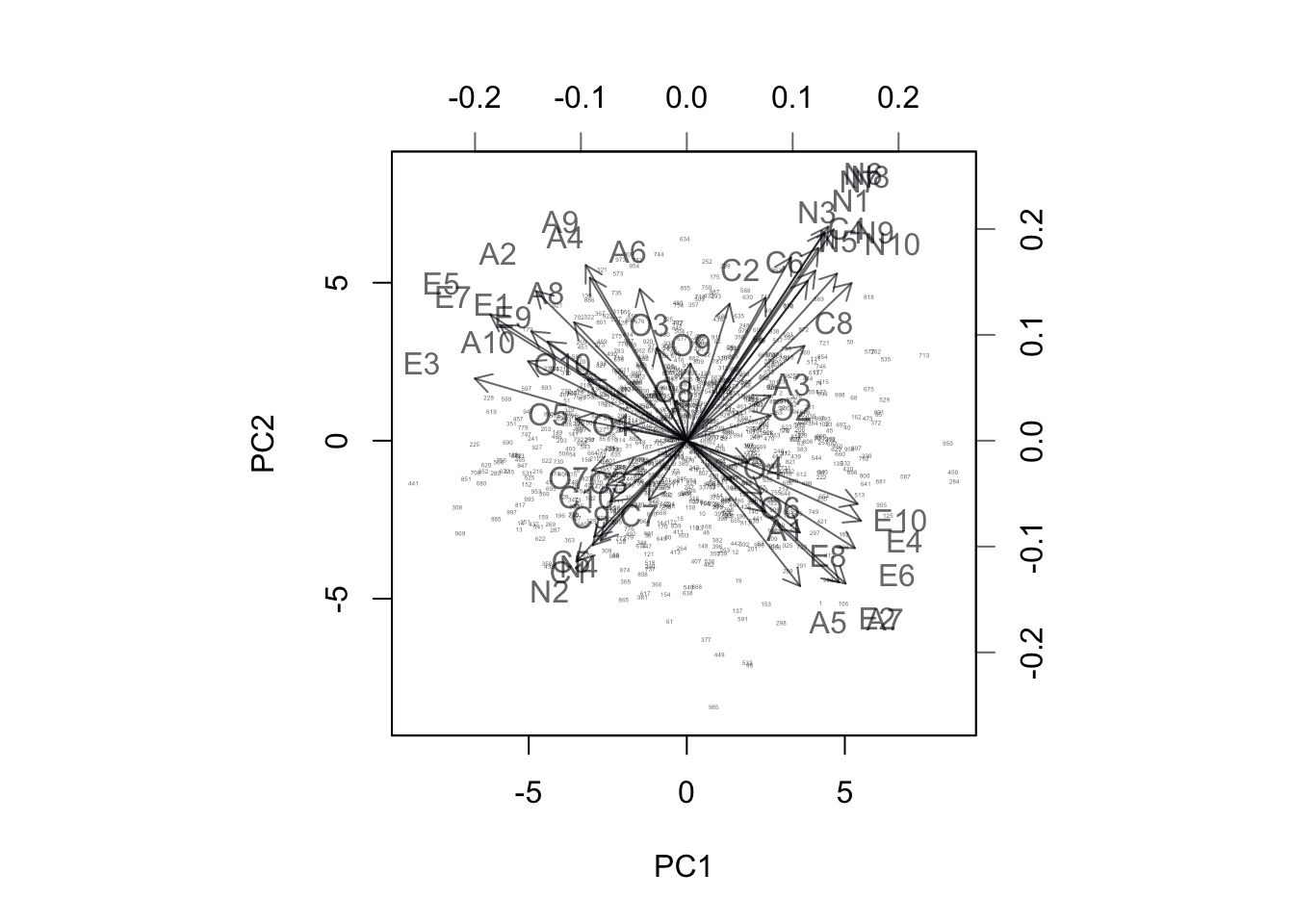

Let’s start with a peek at BiPlots of the first 2 of principal component loadings, prior to rotation. Notice that here I’m not going to bother with any scaling of the factor loadings as I’m not interested in forcing my output to look like SAS’s output. I’m also downsampling the observations because 20,000 is far to many to plot.

biplot(pca.out$x[sample(1:19719,1000),1:2],

pca.out$rotation[,1:2],

cex=c(0.2,1))

Figure 18.5: BiPlot of Projection onto PC1 and PC2

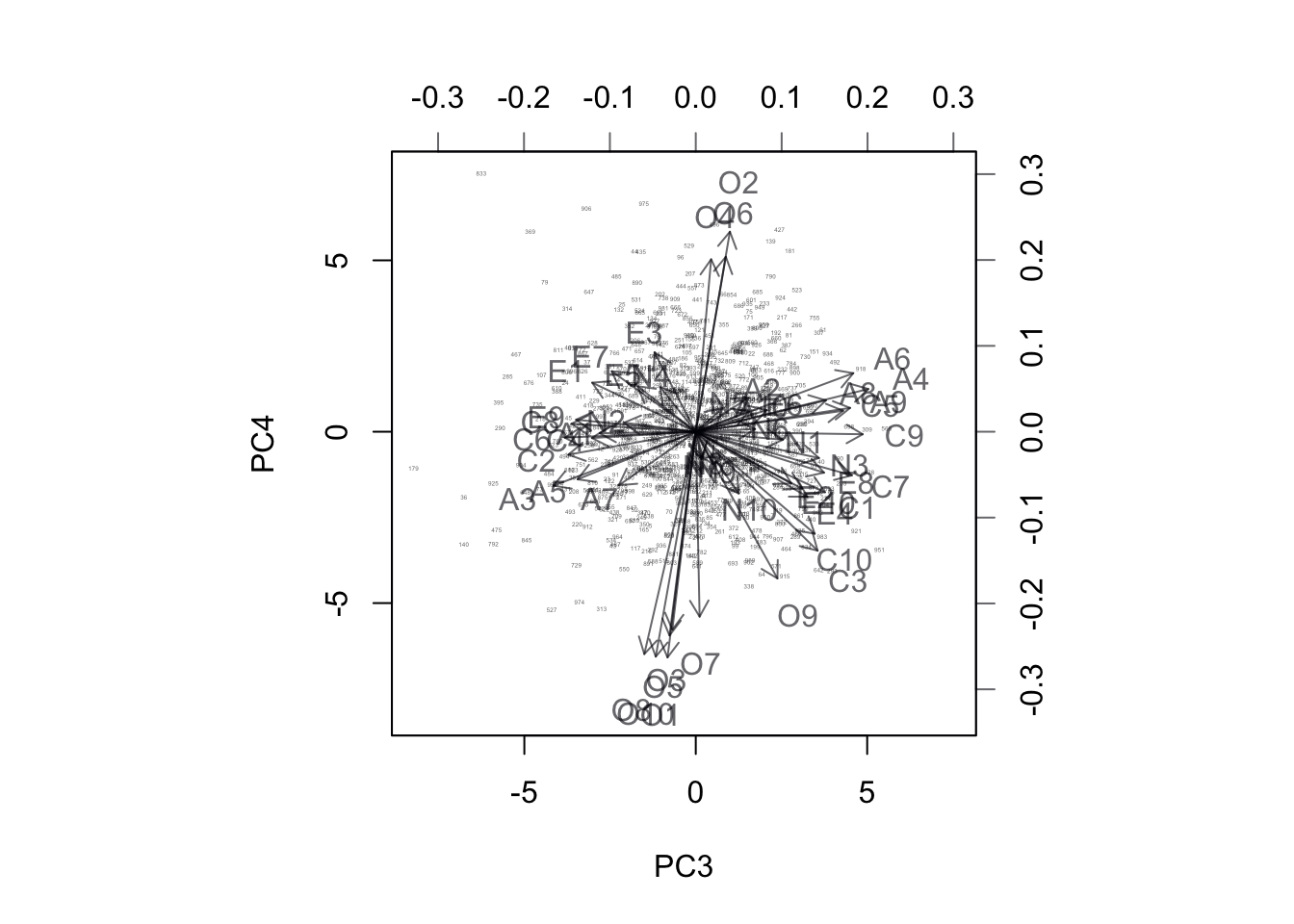

biplot(pca.out$x[sample(1:19719,1000),3:4],

pca.out$rotation[,3:4],

cex=c(0.2,1))

Figure 18.6: BiPlot of Projection onto PC3 and PC4

Let’s see what happens to these biplots after rotation:

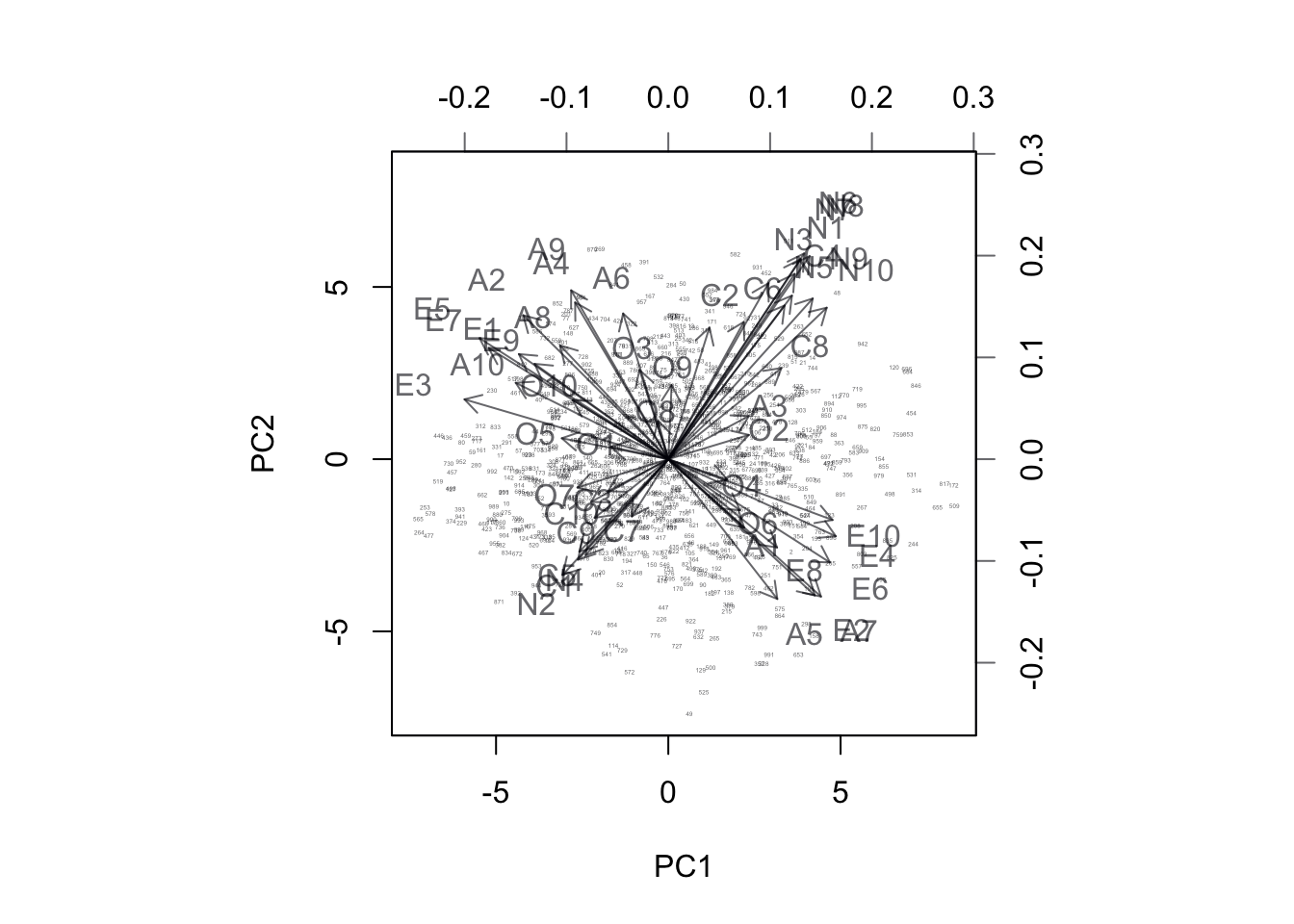

vmax = varimax(pca.out$rotation)

newscores = pca.out$x%*%vmax$rotmat

biplot(newscores[sample(1:19719,1000),1:2],

vmax$loadings[,1:2],

cex=c(0.2,1),

xlab = 'Rotated Axis 1',

ylab = 'Rotated Axis 2')

Figure 18.7: BiPlot of Projection onto Rotated Axes 1,2. Extroversion questions align with axis 1, Neuroticism with Axis 2

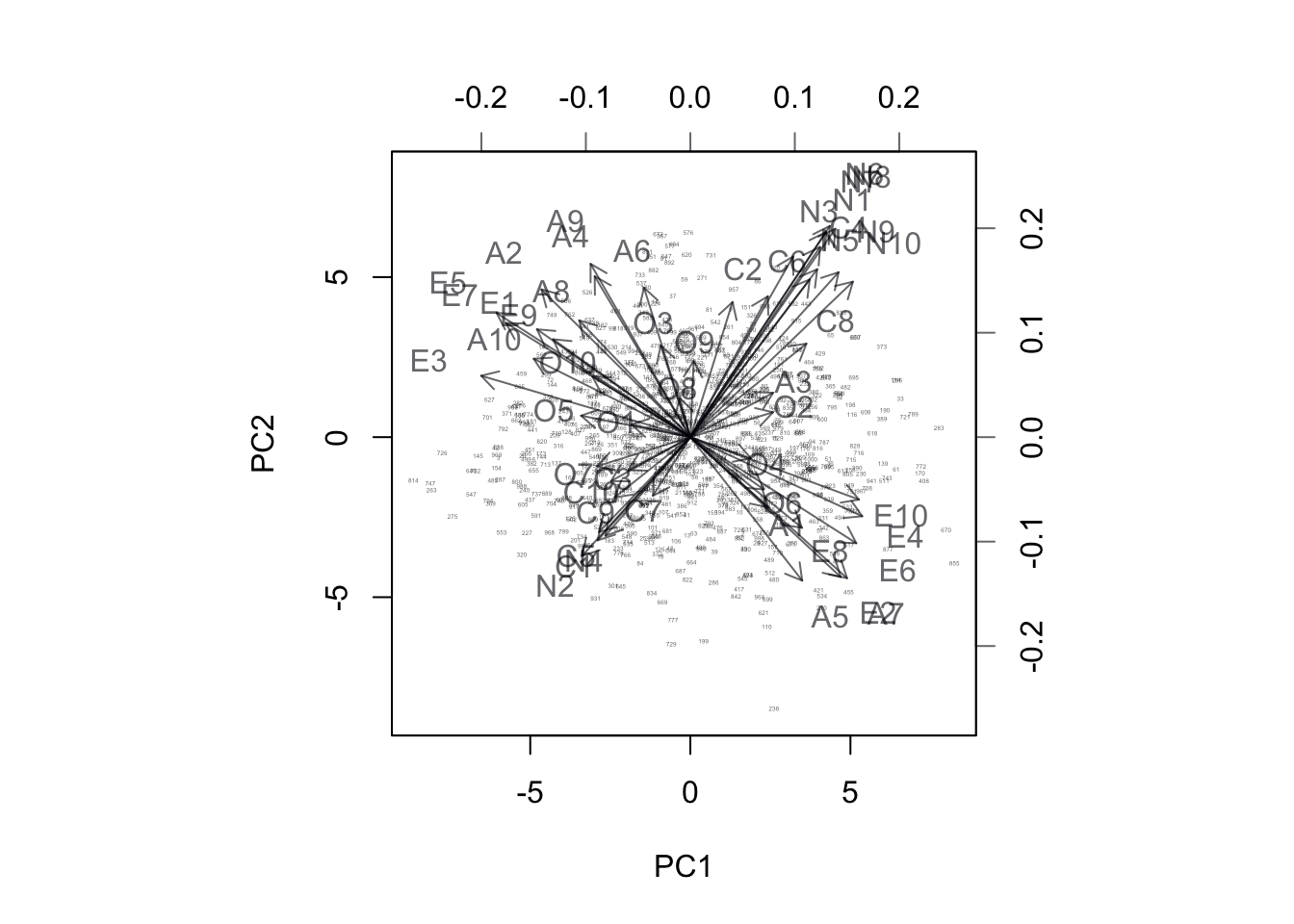

biplot(newscores[sample(1:19719,1000),3:4],

vmax$loadings[,3:4],

cex=c(0.2,1),

xlab = 'Rotated Axis 3',

ylab = 'Rotated Axis 4')

Figure 18.8: BiPlot of Projection onto Rotated Axes 3,4. Agreeableness questions align with axis 3, Openness with Axis 4.

After the rotation, we can see the BiPlots tell a more distinct story. The extroversion questions line up along rotated axes 1, neuroticism along rotated axes 2, and agreeableness and openness are reflected in rotated axes 3 and 4 respectively. The fifth rotated component can be confirmed to represent the last remaining category which is conscientiousness.